Frontline Nurses: Ebola

History

Introduction

From 2014 through 2016, an epidemic of Ebola virus disease unprecedented in scale swept through West Africa. As the largest Ebola outbreak in history and the first to affect urban areas1, the epidemic quickly spread across multiple international borders and became a major global health emergency. A total of 28,616 confirmed and suspected Ebola cases were recorded in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, and the disease resulted in at least 11,310 deaths in those countries.2 The devastation caused by the virus sparked widespread fear throughout West Africa, while numerous factors including cultural practices and histories of conflict in the region contributed to the complexity of the crisis.3

The oral histories collected in this project contain the recommendations and wisdom of frontline nurses and midwives who cared for the sick in one of the deadliest global health disasters in modern times. This essay seeks to contextualize those recommendations within the history of the region and the specific virulence of this disease, and to explore the diverse factors that contributed to the spread of the Ebola virus.4

“When you have war it’s the military, and when you have diseases outbreak it’s the nurses. So we say it that we are now the soldiers. I am a nurse, and this is the only way.” — Joan Shepherd, PhD; Principal, Sierra Leone National School of Midwifery and President, Sierra Leone Midwives Association (as of August 2019)

Regional Context

Legacies of Conflict

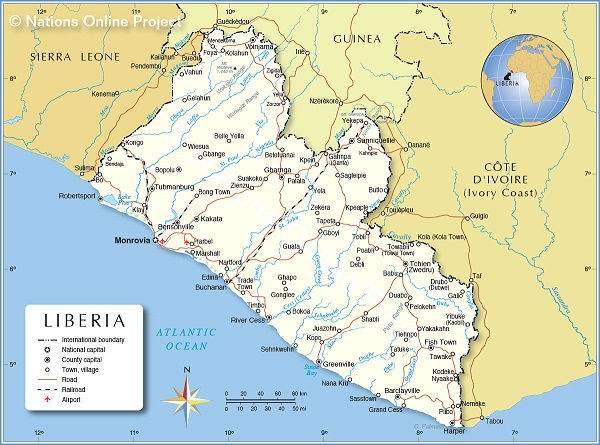

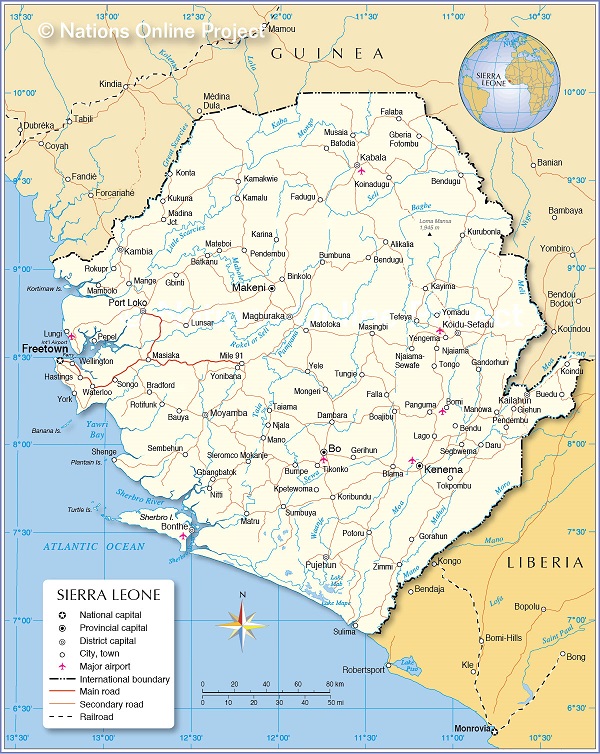

When the Ebola outbreak struck Liberia and Sierra Leone in 2014, the countries were still facing the aftermath of years of civil war and armed conflict that left the populations of both countries with weakened infrastructure and damaged faith in their respective governments. In Liberia, a military coup sparked the first civil war. The conflict took place from 1989 to 1997, leading to the deaths of approximately 250,000 people5 and displacing a further 750,000. A second civil war broke out in 1999, further destabilizing the region. The UN assumed peacekeeping and reintegration efforts in 2003.6 In Sierra Leone, a civil war erupted in 1991, where successive military coups resulted in one of the most intense and concentrated periods of human rights violations in the country’s contemporary history.7 In 2001, the UN intervened to disarm all warring factions. After eleven years, the war finally ended in 2002.

The destruction from these civil wars caused widespread damage to infrastructure, which affected rural areas disproportionately and further limited access to resources in these regions.8

“Sometimes we’ll be on the job and there is an attack, so you have to stay in the hospitals, you stay in the hospital for two or three days, or sometimes even a week without food or without even other things, because you’re not able to leave the ward … for fear you will be seen and attacked.” — Elizabeth K. Lemor; nurse midwife and Directorate of Training, Sierra Leone Ministry of Health (as of August 2019)

Movement Among and Across Populations

High rates of movement across West Africa are largely driven by the importance of seeking economic opportunity. People travel daily for work. This mobility is viewed by some as an economic and political advantage, and the ability to migrate with ease retains social value.9 Women in particular often cross borders to trade in city markets, resulting in increased interpersonal contact at a rate disproportionate to the men of the region.10

High population mobility created significant challenges in controlling the spread of Ebola and impeded contact tracing, especially in rural areas. Incentives were offered to patients and their families to assist with the process of contact tracing; however, patients would often fail to accurately account for all of their recent contacts out of fear and anxiety.11 Additionally, the movements of refugees and other displaced persons increased the average population density in economic and political centers, further accelerating the spread of Ebola.12

“Sierra Leone has a border with Guinea. We have the migration, we have trade between Sierra Leone and Guinea. Sierra Leoneans go to Guinea to buy their goods. And then Guineans come to Sierra Leone. So it’s vice versa.” — Julia W. Kamara; nurse in Monrovia, Liberia who worked in an Ebola Treatment Unit

The Importance of Burial Practices

Of the various community practices that conflicted with measures aiming to curb the spread of Ebola, funeral rites and burial practices proved especially problematic. Common West African burial practices include using water to clean a corpse which other mourners might touch and sleep near.13, 14 The Ministry of Health in Guinea estimated that around 60% of Ebola cases in the country were tied to such practices. Women, the principal caregivers and mourners, were disproportionately affected.15 In Sierra Leone, WHO staff implicated burial and mourning practices in 80% of cases.16

Above: Perret, Martine (2014). “Scene from Ebola Treatment Centre in Port Loko, Sierra Leone.” UN Photo.

As with many communities around the world, the burial of the deceased in unmarked graves, often with multiple bodies in the same grave, violated community norms.17 Burials performed by military personnel were often safer than traditional burials but undignified, while strikes by burial teams led to further complications in the efforts to control the spread of Ebola.18 The shift towards new burial practices was slow. Communities resisted the new measures, as they tended to conflict with social standards up to that point.19 The government of Liberia mandated cremation20 and then recalled the directive after it proved so unpopular that families attempted to bury their deceased relatives in secret.21

“People became very stubborn, even when they would know that a patient has all the signs and symptoms, they would tell you “No, my patient is not going. I don’t want you to burn the body.” … It was really, really difficult … like they thought we were wicked. The medical team, the leadership, the government, we all were wicked people … it was traumatizing for even us. Yes, it was traumatizing for all of us. We had to do what we had to do.” — Mawah Kamara Verdier; registered nurse in Monrovia, Liberia and treasurer of the Liberian Nurses Association (as of August 2019)

The Virulence and Denial of Ebola

The first known cases of Ebola virus disease occurred in 1976 in Central Africa. Different strains of the Ebola virus are thought to naturally reside in fruit bats and periodically spread to humans via close contact with animals. The virus then spreads from person to person via direct contact with the bodily fluids (including blood, saliva, feces, and vomit) of an infected person or an object that has been contaminated with such fluids. The 2014 – 2016 West African epidemic in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia was the largest Ebola outbreak to date.

Though asymptomatic transmission is not thought to occur,22 Ebola mimics other common infectious diseases such as malaria, cholera, and typhoid fever, especially in its early stages. This makes the disease difficult to accurately diagnose without specialized testing. There is no antiviral therapy and treatment is limited to supportive care, such as rehydration and respiratory support. Healthcare workers are at increased risk for infection and strict infection control protocols must be followed to reduce the risk of virus transmission. The necessary protective equipment is bulky and makes it difficult for patients to identify the person who is providing their care. Depending on their particular occupation, healthcare workers were around 21 to 32 times more likely to contract Ebola than those working in other fields,23 though the statistics improved as infection prevention measures were implemented.24 Nurses and their aides and assistants accounted for more than 50% of all infections of health care workers who reported a specific occupation.25

The average fatality rate for Ebola virus disease is 50%.26 Estimates of the overall fatality rate for the West African epidemic range from 40%27 to more than 80%.28 The Ebola virus replicates as the disease progresses, and the viral load is highest when a person dies. This presents particular challenges for funerary practices, as the virus remains viable in a corpse for at least two days following death.29 The virus can also remain active for an unknown length of time in certain bodily fluids, including semen, after an infected person has recovered.30 Current (2020) guidelines direct Ebola survivors and their partners to refrain from unprotected sexual activity until two tests at least one week apart show no evidence of the virus in semen. In the absence of testing, the guidelines recommend waiting at least 12 months before engaging in sexual contact without appropriate protection.31

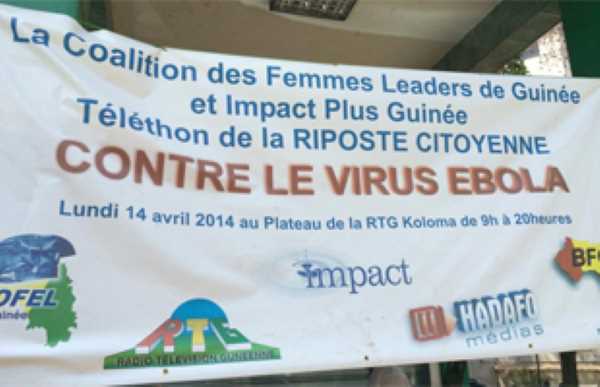

Various widespread theories about the disease32 resulted in mistrust of the medical community,33 while quarantine and other measures aimed at curbing the spread of the virus strained social structures.34 Some frontline healthcare35 and aid36 workers faced hostility even as outreach campaigns worked to combat suspicion with awareness.37

The first Ebola vaccine was approved in late 2019. Clinical trials conducted in West Africa during the epidemic supported the approval of the vaccine, which has since been deployed in the continuing (as of 2020) Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.38

“People believe that the Ebola is not real. That the government wants to get money from the outside world, so they just brought a disease, or say there is Ebola so that support will come in. Some people believed it to be witchcraft. … But from my knowledge as a nurse, I started to tell my staff that we have to be careful. We started wearing gloves for everything we do, we started washing our hands more frequently, and we actually minimized the amount of touches we do. … I understood that Ebola is not what people think it is. Even in my community we organized a group there, and we started going from house to house, we started giving out chlorine, we started giving out Clorox, and we started teaching the people what to do, signs and symptoms, basic things about what to do. We started as fast as possible.” — Ramatta Y. Kogar; nurse in Monrovia, Liberia and chairperson of the Liberian Chapter of the West African College of Nursing (as of August 2019)

Eradicating Ebola

Dangerous Myths

Various instances of violent community resistance were documented throughout the crisis, with Red Cross volunteers and other NGO workers subject to verbal and physical assaults.39 Distrust in the government led to rumors that the disease was being spread by Red Cross volunteers, who were rumored to be spraying schoolchildren with the virus.40

“People were not going to the hospital. They couldn’t trust the health system because at that time. … there was this myth that nurses were part of the disease. … The community never trusted us because they felt that we were lying, we brought the disease, we kill the people. So [we] felt trapped.” — Patience D. Cooper-Tokpah; midwife and nurse in Monrovia, Liberia who supervised the JFK Ebola Treatment Unit

Stigmatization of Healthcare Workers

Healthcare workers experienced significant stigma as a result of their work caring for Ebola patients. There were widespread concerns that healthcare workers were themselves vectors of the disease, and numerous accounts of violence perpetrated against nurses and other healthcare workers during that time have been documented. In 2014 alone, it was reported that Red Cross teams in Guinea encountered violence an average of 10 times a month. Doctors Without Borders (MSF) teams in the country were subjected to violent attacks as well.41 In addition, nurses faced eviction by their landlords and ostracization from their families and communities.

“The stigma was painful. My landlord and my neighbors even went to the police. I was not treating any patients, but because of stigma, most of them went around saying that I had patients because I was working in a treatment center. My landlord even decided to give me notice. I was totally isolated. Nobody would come near me.” — Phaillip Tommy; nurse in Freetown, Sierra Leone who worked at the Hastings Ebola Treatment Center

Gender Roles

There has been some conjecture on the role that gender might have played in the relative death rates of Ebola. Within families, women provide a majority of care, resulting in increased exposure to sick family and community members. During the 2014 crisis, in some regions, women also had the additional responsibility of preparing corpses for burial by bathing and dressing them.42 If the person died from Ebola, such activities are associated with a high risk of contracting the disease as the disease in dead bodies is extremely virulent.43

Traditional roles also influence gender distribution in the healthcare workforce. In sub-Saharan Africa, about 90% of the nursing staff is female, though men hold a majority of leadership positions.44 Consequently, women are most likely to be the frontline caregivers in an epidemic and as a result are most exposed to sick and infectious patients.

During the Ebola outbreak, access to routine healthcare resources was severely limited. For women, this resulted in increased maternal mortality and complications45, 46 and restricted access to contraception.47 Girls who lost their parents to disease were more likely to face child marriage and sexual exploitation.48

The epidemic continues to have lasting effects on women in West Africa. Though income decreased during the epidemic for both men and women, women’s incomes were slower to return to their previous levels.49 Additionally, as childhood vaccination rates dropped during the crisis, it later fell to women to stay home when children became ill with otherwise preventable diseases.50

“But when I was leaving the facility going home, I was worried. Who are these patients I have interacted with? Are they positive? Or are they in the late incubation period where you don’t know that this person is positive?

“I had a child who in 2014 was just four years. How are you going to keep away from that child? Because as soon as I come home from work, “Mama is coming home!” He’s going to rush to me and hold me tight. So when I got home, I would say, “When I come from work, nobody come around me. Stay away.” But it was difficult because those were our kids. When you are sitting as a mother, that child will come unknowingly, come and rub on you. It was difficult. But we did what we could do.” — Wilhelmina W.G. Flomo; registered midwife in Monrovia, Liberia and president of the Liberia Midwives Association (as of August 2019)

Maternal Health During the Outbreak

Available data suggest that women who contract Ebola while pregnant face a higher risk of death and will almost certainly lose their child. There are isolated reports of infants born to mothers with Ebola who survived, but such instances are extremely rare.51, 52 Estimations of maternal mortality for women with Ebola range from 74-100%, and average around 86%.53

In West African countries, the percentage of deliveries attended by skilled healthcare workers decreased during the epidemic.54 Healthcare facilities closed and healthcare workers died, straining further an already-stressed system. Rumors about nefarious actions of medical workers and fear of contracting Ebola also kept women from seeking skilled care at healthcare facilities.55 During the crisis, more women sought traditional birth attendants and healers.56 Some believe that such practices had the unintended consequence of further spreading the disease.57

For health workers, the volume of bodily fluids present during delivery presents an inherently hazardous environment. Ebola increases the risk of bleeding, already a potential complication of childbirth. For women, the symptoms of Ebola can overlap with other ailments common to pregnancy, complicating timely diagnosis.58 Medical care of pregnant women with Ebola was also impeded by the presence of malaria and sepsis.59

The outbreak also halted ongoing efforts and progress in Liberia to improve maternal and child health.60 In Sierra Leone, the number of women accessing maternal care decreased. Among those who could access care, stillbirths and maternal mortality increased.61

In addition to the structural barriers impeding maternal care during an epidemic, there is also some theorizing that pregnant women are particularly susceptible to infection due to physiological changes in immune function. The virus has been detected in breast milk, and the placenta may also act as a “viral reservoir.” Case reports have shown that healthy pregnancies and deliveries are possible following recovery from Ebola, but the extent of the impact of the disease on future pregnancies remains unclear.62

“There was a house, and all the relatives were outside screaming, “Oh, she’s in labor. We think the baby is coming. Few minutes.” I didn’t even have time to put on the gloves. She was pushing the baby on the couch. So I had to catch the baby. But while I was doing the delivery I was saying to myself, oh my goodness. What if I get infected? But my key objective by then was not even thinking about infection. I was just thinking that the baby should not drop onto the floor. I improvised. I had some polythene sheets, plastic aprons, and I used that to deliver the baby. A few minutes later the ambulance arrived, and the nurses said, “Can we take over?” I said, “No, since I’m already in a pool of blood and I have already handled the kid—if there’s any risk involved I want to minimize the risk,” I said. “So let me just complete the delivery.” I delivered the baby, cut the cord, cleaned up the mother and the ground. My shoes were all soaked with blood, so I had to put some chlorine on my boots, my shoes, wash my hands. And then it was after that I said my goodness, that was a big risk, but at the same time my instinct as a midwife, I couldn’t stand to see a woman pushing a baby and the baby—and I was there.” — Joan Shepherd, PhD; Principal, Sierra Leone National School of Midwifery and President, Sierra Leone Midwives Association (as of August 2019)

Impact on General Healthcare During Crisis

The Ebola crisis caused widespread shutdowns and a limitation of healthcare services to Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs), especially in urban areas. The delivery of other healthcare services was significantly slowed. The CDC estimated that due to reduced services, 10,600 more people died from HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone than during a comparable period before the outbreak.63

Women seeking maternal care had the greatest difficulty accessing health services. Despite the concentration of resources in urban areas, the disease had a disproportionate effect on the ability of urban residents to receive healthcare. In Liberia, only about 20-30% of people who sought healthcare in urban areas were able to access it, compared with about 70-80% of people who were able to do so in rural areas. In rural counties, most residents (nearly 60%) noted fear of Ebola as the major impediment to obtaining care. However, in urban areas, the largest obstacles were lack of healthcare facilities due to closure (35%) and the refusal of healthcare workers to care for patients (32%), followed by fear of becoming infected Ebola while seeking care (24%).64

“In terms of maternity services, for example, I mean, if women were pregnant, they were still pregnant, and they had to go and deliver, and that was the fact.” — Margaret Loma Phiri; nurse midwife from Malawi who worked in Sierra Leone in 2015 on behalf of the WHO

After the Crisis

End of the Outbreak

The outbreak did not end suddenly; it trailed off over time. With each day that passed with no new cases being reported, a 21-day countdown would begin to ensure that no patients had gone undetected. Even so, in both Sierra Leone and Liberia, the end of the outbreak was declared prematurely on multiple occasions. Liberia was declared Ebola-free for the fourth time on June 9, 2016. On March 7, 2016, Sierra Leone was declared Ebola-free for the second time. On June 1, 2016, Guinea declared Ebola-free for the second time. On March 29, 2016, the WHO declared the end of the Public Health Emergency of International Concern.65

The crisis has had a lasting effects in the region. The loss of healthcare workers resulted in a shortage of healthcare services. Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone faced heavy budget deficits. The World Bank estimates the financial impact of the Ebola epidemic on West Africa at $2.8 billion, comprised of a toll of $600 million in Guinea, $300 million in Liberia, and $1.9 billion in Sierra Leone. Budgetary deficits in 2015 were estimated to constitute 8.5% of the GDP in Liberia, 9.4 % in Guinea, and 4.8% in Sierra Leone.66

Models describing the effects of the loss of doctors, nurses, and midwives on various health outcomes show the largest effects on maternal mortality, with predicted increases of 38% in Guinea, 74% in Sierra Leone, and 111% in Liberia compared to pre-Ebola statistics. These estimates indicate the loss of an additional 4,022 women per year in childbirth. The resulting maternal mortality rates would rival those from the height of conflict periods, including figures from 2000 in Guinea and Sierra Leone, and 1995 in Liberia.67 Children missed more than eight months of school and experienced a 30% decline in routine immunizations. Throughout West Africa, 17,300 children were left without one or both of their parents due to losses from Ebola.68

“I saw children die. I saw women die. I saw men die. I saw babies die. People used to die like you can’t imagine. Yes. It was terrible to the look of eyes, it was terrible to the ears, and when you confront it sometimes say God, have mercy.” — Jestina T. Clarke; nurse midwife at Redemption Hospital in Monrovia, Liberia

Continued Infection Protection Control

Neither Sierra Leone69 nor Liberia70 had national guidelines for infection prevention control (IPC) prior to the Ebola outbreak. A lack of resources, including gloves, disinfectants, and reliable electricity, presents an ongoing challenge to continued implementation of such measures. Regular use of IPC also requires a shift of norms within healthcare institutions where such practices were not previously common.71

Above: Gborie, S. WHO.

Sierra Leone and Liberia have both since increased the number of facilities that meet IPC standards and employ staff trained in IPC. Regular hand-washing practices have increased, which is crucial for curbing the spread of common and uncommon infectious diseases. Health messaging efforts have also been put into practice to address widespread mistrust.72

By 2016, Sierra Leone had not yet implemented comprehensive statewide biosafety training, but had identified the need for such a program. In 2018, the country launched a National Action Plan for Health Security to address issues raised in a 2016 WHO report.73 At that time, the WHO stated that the country’s ability to isolate and transport infectious patients was “commendable.” New IPC certificate courses74 and facility assessments have been implemented to address the need for regular infection prevention measures. At the end of 2018, IPC compliance at district hospitals was measured at nearly 85% using the new assessment tool. 75

In Liberia, public healthcare facilities have shown greater increase in IPC practices after the Ebola epidemic than private facilities.76 There is a national program for infection prevention that directly resulted from the epidemic, and the WHO reports a “strong foundation” for use of IPC measures and “robust experience” in responding to a public health emergency. In addition, the WHO states that Liberia has made “significant progress post-Ebola in all domains of human and public health.”

Maternal mortality rates in Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea had all been experiencing downward trends prior to Ebola, despite a consistent scarcity of resources.77 The epidemic seriously impeded such progress.78 Sierra Leone and Liberia had some of the smallest healthcare workforces in the world prior to the epidemic, and the loss of workers to Ebola further reduced those numbers. In addition, university closures delayed the graduation of trained healthcare workers.79

The WHO reports limited infrastructure in Guinea for infection prevention. IPC training during the epidemic was found to increase IPC knowledge,80 and those who participated in training sessions were encouraged to share their knowledge with their colleagues.81 In Guinea, there had been an increase in women accessing prenatal care before the epidemic, which declined during the crisis. These numbers declined during the crisis and rose again immediately following the outbreak, but they remain short of their pre-Ebola levels. Childhood vaccination rates also fell during the outbreak, and vaccine coverage was reduced after the crisis.82

“Another lesson, or one last negative part, is we tend to forget too soon. When things are no more, we feel that all is well. Instead of being proactive, we most of time become retroactive. That is, we know that you need to take your IPC measures at all times. Do not wait for a situation to come before you say, “Oh, let me take IPC measures.” It could be too late. You could be infected already. So, instead of just waiting for Ebola outbreak or another outbreak before we know that we as health workers should take precautions … We need to learn from the Ebola episode.” — Wilhelmina W.G. Flomo; registered midwife in Monrovia, Liberia and president of the Liberia Midwives Association (as of August 2019)

Erica Andersen, Ming Pei, and Thomas Peterson; adapted in part from the work of Hannah Bender.

Notes

-

2014-2016 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa. (2019, March 08). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html ↩︎

-

Ebola outbreak 2014-2016. (2014 - 2016). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/en/ ↩︎

-

Factors that contributed to undetected spread of the Ebola virus and impeded rapid containment. (2015, January). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/one-year-report/factors/en ↩︎

-

The interviews conducted for this oral history were limited to Sierra Leone and Liberia; however, this was a regional pandemic and thus some information pertaining to Guinea has been included as well. ↩︎

-

Liberia country profile. (2018, January 22). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13729504 ↩︎

-

Palmisano, L., & Momodu, S. (2013, January 04). UNHCR completes repatriation of 155,000 Liberians. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/makingdifference/2013/1/50e6af089/unhcr-completes-repatriation-155000-liberians.html ↩︎

-

Shocking War Crimes in Sierra Leone. (1999, June 24). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.hrw.org/news/1999/06/24/shocking-war-crimes-sierra-leone ↩︎

-

Hoeffler, A. (2002, February 17). Challenges of Infrastructure Rehabilitation and Reconstruction In War-affected Economies (Economic Research Papers, Working Paper No. 48). African Development Bank. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/document/working-paper-48-challenges-of-infrastructure-rehabilitation-and-reconstruction-in-war-affected-economies-9004 ↩︎

-

Charrière, F., & Frésia, M. (2008). West Africa as a Migration and Protection area (Report). United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees (UNHCR). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.unhcr.org/49e479c311.pdf ↩︎

-

Hogan, C. (2014, August 14). Ebola striking women more frequently than men. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/2014/08/14/3e08d0c8-2312-11e4-8593-da634b334390_story.html ↩︎

-

Saurabh, S., & Prateek, S. (2017). Role of contact tracing in containing the 2014 Ebola outbreak: A review. African Health Sciences, 17(1), 225-236. doi:10.4314/ahs.v17i1.28 ↩︎

-

Charrière, F., & Frésia, M. (2008). West Africa as a Migration and Protection area (Report). United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees (UNHCR). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.unhcr.org/49e479c311.pdf ↩︎

-

Factors that contributed to undetected spread of the Ebola virus and impeded rapid containment. (2015, January). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/one-year-report/factors/en ↩︎

-

Manguvo, A., & Mafuvadze, B. (2015). The impact of traditional and religious practices on the spread of Ebola in West Africa: time for a strategic shift. The Pan African medical journal, 22 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 9. https://doi.org/10.11694/pamj.supp.2015.22.1.6190 ↩︎

-

Barriers to rapid containment of the Ebola outbreak. (2014, August 11). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/overview-august-2014/en/ ↩︎

-

Factors that contributed to undetected spread of the Ebola virus and impeded rapid containment. (2015, January). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/one-year-report/factors/en ↩︎

-

Nielsen, C. F., PhD, Kidd, S., MD, Sillah, A. R., PhD, MD, Davis, E., Mermin, J., MD, & Kilmarx, P. H. (2015, January 16). Improving Burial Practices and Cemetery Management During an Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic — Sierra Leone, 2014 (1st ed., Vol. 64, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, pp. 20-27). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6401a6.htm ↩︎

-

Factors that contributed to undetected spread of the Ebola virus and impeded rapid containment. (2015, January). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/one-year-report/factors/en ↩︎

-

Manguvo, A., & Mafuvadze, B. (2015). The impact of traditional and religious practices on the spread of Ebola in West Africa: time for a strategic shift. The Pan African medical journal, 22 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 9. https://doi.org/10.11694/pamj.supp.2015.22.1.6190 ↩︎

-

Baker, A. (2014, October 07). Liberia Burns its Bodies as Ebola Fears Run Rampant. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://time.com/3478238/ebola-liberia-burials-cremation-burned/ ↩︎

-

Paye-Layleh, J. (2014, December 31). Liberia eases up on cremation order for Ebola victims - The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.bostonglobe.com/news/world/2014/12/31/liberia-eases-cremation-order-for-ebola-victims/COE4dzBojdSxF7N72FbxfN/story.html ↩︎

-

Mbala, P., Baguelin, M., Ngay, I., Rosello, A., Mulembakani, P., Demiris, N., Edmunds, W. J., & Muyembe, J. J. (2017). Evaluating the frequency of asymptomatic Ebola virus infection. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 372(1721), 20160303. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0303 ↩︎

-

Health worker Ebola infections in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone (Preliminary Report). (2015, May 21). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/171823/WHO_EVD_SDS_REPORT_2015.1_eng.pdf?sequence=1 ↩︎

-

Ebola health worker infections. (n.d.). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.who.int/features/ebola/health-care-worker/en/ ↩︎

-

Health worker Ebola infections in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone (Preliminary Report). (2015, May 21). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/171823/WHO_EVD_SDS_REPORT_2015.1_eng.pdf?sequence=1 ↩︎

-

Ebola virus disease. (2020, February 10). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ebola-virus-disease ↩︎

-

Wappes, J. (2018, December 31). US health worker monitored as DRC Ebola nears 600 cases. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2018/12/us-health-worker-monitored-drc-ebola-nears-600-cases ↩︎

-

Forna, A., Nouvellet, P., Dorigatti, I., & Donnelly, C. A. (2019). Case Fatality Ratio Estimates for the 2013–2016 West African Ebola Epidemic: Application of Boosted Regression Trees for Imputation. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 70(12), 2476-2483. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz678 ↩︎

-

Vetter, P., Fischer, W. A., Schibler, M., Jacobs, M., Bausch, D. G., & Kaiser, L. (2016). Ebola Virus Shedding and Transmission: Review of Current Evidence. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 214(Suppl 3), S177-S184. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw254 ↩︎

-

Transmission, Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever. (2019, November 05). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/transmission/index.html ↩︎

-

Interim advice on the sexual transmission of the Ebola virus disease. (2016, January 21). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/rtis/ebola-virus-semen/en/ ↩︎

-

Estrada, C. (2014, June 24). Ebola, snakes and witchcraft: Stopping the deadly disease in its tracks in West Africa. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.ifrc.org/es/noticias/noticias/africa/sierra-leone/ebola-snakes-and-witchcraft-stopping-the-deadly-disease-in-its-tracks-in-west-africa-66215/ ↩︎

-

Manguvo, A., & Mafuvadze, B. (2015). The impact of traditional and religious practices on the spread of Ebola in West Africa: time for a strategic shift. The Pan African medical journal, 22 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 9. https://doi.org/10.11694/pamj.supp.2015.22.1.6190 ↩︎

-

Pellecchia, U., Crestani, R., Decroo, T., Bergh, R. V., & Al-Kourdi, Y. (2015). Social Consequences of Ebola Containment Measures in Liberia. Plos One, 10(12). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143036 ↩︎

-

Maxmen, A. (2019, June 04). Ebola cases pass 2,000 as crisis escalates. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01735-0 ↩︎

-

Buchanan, E. (2015, February 23). Ebola Crisis: Red Cross workers attacked as virus conspiracies create panic in Guinea. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/ebola-crisis-red-cross-workers-attacked-virus-conspiracies-create-panic-guinea-1488865 ↩︎

-

Dizikes, P. (2020, February 26). How door-to-door canvassing slowed an epidemic. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from http://news.mit.edu/2020/how-door-to-door-canvassing-slowed-epidemic-ebola-0227 ↩︎

-

Branswell, H. (2020, January 07). The inside story of how scientists produced an Ebola vaccine. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.statnews.com/2020/01/07/inside-story-scientists-produced-world-first-ebola-vaccine/ ↩︎

-

Red Cross Red Crescent denounces continued violence against volunteers working to stop the spread of Ebola. (2015, February 12). Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.ifrc.org/en/news-and-media/press-releases/africa/guinea/red-cross-red-crescent-denounces-continued-violence-against-volunteers-working-to-stop-the-spread-of-ebola/ ↩︎

-

Buchanan, E. (2015, February 23). Ebola Crisis: Red Cross workers attacked as virus conspiracies create panic in Guinea. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/ebola-crisis-red-cross-workers-attacked-virus-conspiracies-create-panic-guinea-1488865 ↩︎

-

Samb, S., & Bavier, J. (2015, February 14). Crowds attack Ebola facility, health workers in Guinea. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-ebola-guinea/crowds-attack-ebola-facility-health-workers-in-guinea-idUSKBN0LI0G920150214 ↩︎

-

Nkangu, M. N., Olatunde, O. A., & Yaya, S. (2017). The perspective of gender on the Ebola virus using a risk management and population health framework: a scoping review. Infectious diseases of poverty, 6(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-017-0346-7 ↩︎

-

Brainard, J., Hooper, L., Pond, K., Edmunds, K., & Hunter, P. R. (2015). Risk factors for transmission of Ebola or Marburg virus disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 45(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv307 ↩︎

-

Munjanja, O. K., Kibuka, S., & Dovlo, D. (2005). The nursing workforce in sub-Saharan Africa (Issue7, Report). Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.ghdonline.org/uploads/The_nursing_workforce_in_sub-Saharan_Africa.pdf ↩︎

-

Jones, S. A., Gopalakrishnan, S., Ameh, C. A., White, S., & van den Broek, N. R. (2016). ‘Women and babies are dying but not of Ebola’: the effect of the Ebola virus epidemic on the availability, uptake and outcomes of maternal and newborn health services in Sierra Leone. BMJ Global Health, 1(3), e000065. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000065 ↩︎

-

Shannon, F. Q., 2nd, Horace-Kwemi, E., Najjemba, R., Owiti, P., Edwards, J., Shringarpure, K., Bhat, P., & Kateh, F. N. (2017). Effects of the 2014 Ebola outbreak on antenatal care and delivery outcomes in Liberia: a nationwide analysis. Public health action, 7(Suppl 1), S88–S93. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.16.0099 ↩︎

-

Bietsch, K., Williamson, J., & Reeves, M. (2020). Family Planning During and After the West African Ebola Crisis. Studies in Family Planning, 51(1), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12110 ↩︎

-

Korkoyah, D. T., & Wreh, F. F. (2015). The Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection, Monrovia Liberia. Retrieved from https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/rr-ebola-impact-women-men-liberia-010715-en.pdf ↩︎

-

Gupta, A. H. (2020, March 12). Why Women May Face a Greater Risk of Catching Coronavirus. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/12/us/women-coronavirus-greater-risk.html ↩︎

-

Lewis, H. (2020, April 1). The Coronavirus Is a Disaster for Feminism. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/03/feminism-womens-rights-coronavirus-covid19/608302/ ↩︎

-

Guidance for Screening and Caring for Pregnant Women with Ebola Virus Disease for Healthcare Providers in U.S. Hospitals. (2018, May 30). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/clinicians/evd/pregnant-women.html ↩︎

-

Baraka, N. K., Mumbere, M., & Ndombe, E. (2019). One month follow up of a neonate born to a mother who survived Ebola virus disease during pregnancy: a case report in the Democratic Republic of Congo. BMC Pediatrics, 19(1), 202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1584-6 ↩︎

-

Bebell, L. M., Oduyebo, T., & Riley, L. E. (2017). Ebola virus disease and pregnancy: A review of the current knowledge of Ebola virus pathogenesis, maternal, and neonatal outcomes. Birth defects research, 109(5), 353–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.23558 ↩︎

-

Shannon, F. Q., 2nd, Horace-Kwemi, E., Najjemba, R., Owiti, P., Edwards, J., Shringarpure, K., Bhat, P., & Kateh, F. N. (2017). Effects of the 2014 Ebola outbreak on antenatal care and delivery outcomes in Liberia: a nationwide analysis. Public health action, 7(Suppl 1), S88–S93. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.16.0099 ↩︎

-

Hayden, E. C. (2015, March 4). Maternal health: Ebola's lasting legacy. Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.nature.com/news/maternal-health-ebola-s-lasting-legacy-1.17036 ↩︎

-

McQuilkin, P. A., Udhayashankar, K., Niescierenko, M., & Maranda, L. (2017). Health-Care Access during the Ebola Virus Epidemic in Liberia. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 97(3), 931–936. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.16-0702 ↩︎

-

Manguvo, A., & Mafuvadze, B. (2015). The impact of traditional and religious practices on the spread of Ebola in West Africa: time for a strategic shift. The Pan African medical journal, 22 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 9. https://doi.org/10.11694/pamj.supp.2015.22.1.6190 ↩︎

-

Hayden, E. C. (2015, March 4). Maternal health: Ebola's lasting legacy. Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.nature.com/news/maternal-health-ebola-s-lasting-legacy-1.17036 ↩︎

-

Bebell, L. M., Oduyebo, T., & Riley, L. E. (2017). Ebola virus disease and pregnancy: A review of the current knowledge of Ebola virus pathogenesis, maternal, and neonatal outcomes. Birth defects research, 109(5), 353–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.23558 ↩︎

-

Iyengar P, Kerber K, Howe CJ, Dahn B. Services for Mothers and Newborns During the Ebola Outbreak in Liberia: The Need for Improvement in Emergencies. PLOS Currents Outbreaks. 2015 Apr 16 . Edition 1. doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.4ba318308719ac86fbef91f8e56cb66f. ↩︎

-

Jones, S. A., Gopalakrishnan, S., Ameh, C. A., White, S., & van den Broek, N. R. (2016). ‘Women and babies are dying but not of Ebola’: the effect of the Ebola virus epidemic on the availability, uptake and outcomes of maternal and newborn health services in Sierra Leone. BMJ Global Health, 1(3), e000065. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000065 ↩︎

-

Haddad, L. B., Horton, J., Ribner, B. S., & Jamieson, D. J. (2018). Ebola Infection in Pregnancy: A Global Perspective and Lessons Learned. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology, 61(1), 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000332 ↩︎

-

Cost of the Ebola Epidemic: Indirect Impact of Ebola on Health Care. (n.d.). Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/pdf/indirect-impact-healthcare.pdf ↩︎

-

McQuilkin, P. A., Udhayashankar, K., Niescierenko, M., & Maranda, L. (2017). Health-Care Access during the Ebola Virus Epidemic in Liberia. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 97(3), 931–936. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.16-0702 ↩︎

-

Ebola is no longer a public health emergency. (2016, March 29). Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/29-03-2016-statement-on-the-9th-meeting-of-the-ihr-emergency-committee-regarding-the-ebola-outbreak-in-west-africa ↩︎

-

2014-2015 West Africa Ebola Crisis: Impact Update. (n.d.). Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/macroeconomics/publication/2014-2015-west-africa-ebola-crisis-impact-update ↩︎

-

Evans, D. K., Goldstein, M., & Popova, A. (2015). Health-care worker mortality and the legacy of the Ebola epidemic. The Lancet. Global health, 3(8), e439–e440. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00065-0 ↩︎

-

Cost of the Ebola Epidemic: Impact of Ebola on Children. (n.d.). Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/pdf/impact-ebola-children.pdf ↩︎

-

CDC Global Health - Stories - Improving Infection Prevention and Control in Sierra Leone. (2015, July 20). Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/stories/ipc_sierra_leone.html ↩︎

-

Cooper, C., Fisher, D., Gupta, N., MaCauley, R., & Pessoa-Silva, C. L. (2016). Infection prevention and control of the Ebola outbreak in Liberia, 2014-2015: key challenges and successes. BMC medicine, 14, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0548-4 ↩︎

-

World Health Organization. (2015). Final Report: Infection Prevention and Control Recovery Plans and Implementation: Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone Inter-country Meeting . Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/204370/WHO_HIS_SDS_2015.23_eng.pdf?sequence=1 ↩︎

-

Center for Strategic and International Studies Global Health Policy Center. (n.d.). How Did Ebola Impact Maternal and Child Health in Liberia and Sierra Leone? Retrieved from https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-did-ebola-impact-maternal-and-child-health-liberia-and-sierra-leone ↩︎

-

Sierra Leone, Ministry of Health and Sanitation. Sierra Leone National Action Plan for Health Security (2018-2022). Retrieved from https://www.afro.who.int/publications/sierra-leone-national-action-plan-health-security-2018-2022 ↩︎

-

“USAID’s Achievement in Promoting Infection Prevention Control in Sierra Leone” (2017, December 19). Retrieved from https://sl.usembassy.gov/usaids-achievement-in-promoting-infection-prevention-control-in-sierra-leone/ ↩︎

-

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Sierra Leone Annual Report: A Year in Focus 2018. Retrieved from https://www.afro.who.int/publications/who-sierra-leone-2018-annual-report ↩︎

-

Tremblay, N., Musa, E., Cooper, C., Van den Bergh, R., Owiti, P., Baller, A., Siafa, T., Woldeyohannes, D., Shringarpure, K., & Gasasira, A. (2017). Infection prevention and control in health facilities in post-Ebola Liberia: don't forget the private sector!. Public health action, 7(Suppl 1), S94–S99. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.16.0098 ↩︎

-

Hayden, E. C. (2015, March 4). Maternal health: Ebola's lasting legacy. Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.nature.com/news/maternal-health-ebola-s-lasting-legacy-1.17036 ↩︎

-

Government of Sierra Leone. (n.d.). National Nursing And Midwifery Strategic Plan 2019-2023. Retrieved from https://sierraleone.unfpa.org/en/publications ↩︎

-

Center for Strategic and International Studies Global Health Policy Center. (n.d.). How Did Ebola Impact Maternal and Child Health in Liberia and Sierra Leone? Retrieved from https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-did-ebola-impact-maternal-and-child-health-liberia-and-sierra-leone ↩︎

-

Soeters, H. M., Koivogui, L., de Beer, L., Johnson, C. Y., Diaby, D., Ouedraogo, A., … Diallo, A. O. (2018). Infection prevention and control training and capacity building during the Ebola epidemic in Guinea. PLOS ONE, 13(2), e0193291. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193291 ↩︎

-

Keïta, M., Camara, A. Y., Traoré, F., Camara, M. E., Kpanamou, A., Camara, S., … Subissi, L. (2018). Impact of infection prevention and control training on health facilities during the Ebola virus disease outbreak in Guinea. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 547. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5444-3 ↩︎

-

Delamou, A., Ayadi, A., Sidibe, S., Delvaux, T., Camara, B. S., Sandouno, S. D., Beavogui, A. H., Rutherford, G. W., Okumura, J., Zhang, W. H., & De Brouwere, V. (2017). Effect of Ebola virus disease on maternal and child health services in Guinea: a retrospective observational cohort study. The Lancet. Global health, 5(4), e448–e457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30078-5 ↩︎